When is a Question Better than an Answer?

Six good questions to ask and a helpful resource to use when engaging neighbors on hot topics.

09/5/23

John Stonestreet

It can be intimidating to engage our neighbors on cultural issues these days. It seems that every conversation is a potential minefield where the slightest wrong word can get you banished from polite society as a bigot or “hater.” This is where we can take a lesson from two of the greatest teachers of all time, Jesus and Socrates. Both were masters of their craft, and both used questions to lead their listeners to the answers they sought.

Here are six questions I’ve found extremely helpful to create the sort of dialogue we should desire about issues of faith and culture.

First: What do you mean by that? The battle of ideas is always tied up in the battle over the definition of words. Thus, it’s vital in any conversation to clarify the terms being used. For example, the most important thing to clarify about “same-sex marriage” is the definition of marriage. When the topic comes up, it’s best to say, “Hold on, before we go too far into what kind of unions should be considered marriage, what do you mean by marriage?” Often, when it comes to these crucial issues, we’re all using the same vocabulary, but rarely the same dictionary.

Here’s a second question: How do you know that is true? Too often, assertions are mistaken for arguments, and there’s a vast difference between the two. An assertion is a definitive statement made about the nature of reality. An argument is presented to back up an assertion. By asking “how do you know that’s true?” we’ll move the conversation beyond dueling assertions to why those assertions should be taken seriously.

For example, it’s a common assertion that the Church has always been an obstacle to education and science, but this is just a legend. In reality, not only did schools pop up everywhere churches went, but a host of scientists, past and present, have been devout believers.

Here’s a third question: Where did you get this information? Once arguments are offered, it’s important to ensure the arguments are valid. For example, news reports love to shout headlines about some study that shows same-sex couples are better parents than straight couples.

However, this quickly repeated talking point is based on limited studies that are flawed. More and broader-based studies suggest the exact opposite.

The fourth question: How did you come to this conclusion? Behind the individuals you are talking with and their convictions, is a story … a personal story. If you know that story, it may make more sense why they don’t find your views plausible. Plus, it will help you remember that the person you’re talking with is a real, image-of-God bearing person.

The final two questions: What if you’re wrong? and What if you’re right? It’s easy to sit back and make claims about the world, but what happens when those claims get out into that world? Ideas have consequences that are always worth considering. For example, what happens if marijuana isn’t as harmless as people say it is, or what if we tell kids that they’re born in the wrong body? That’s a big risk to play with the next generation.

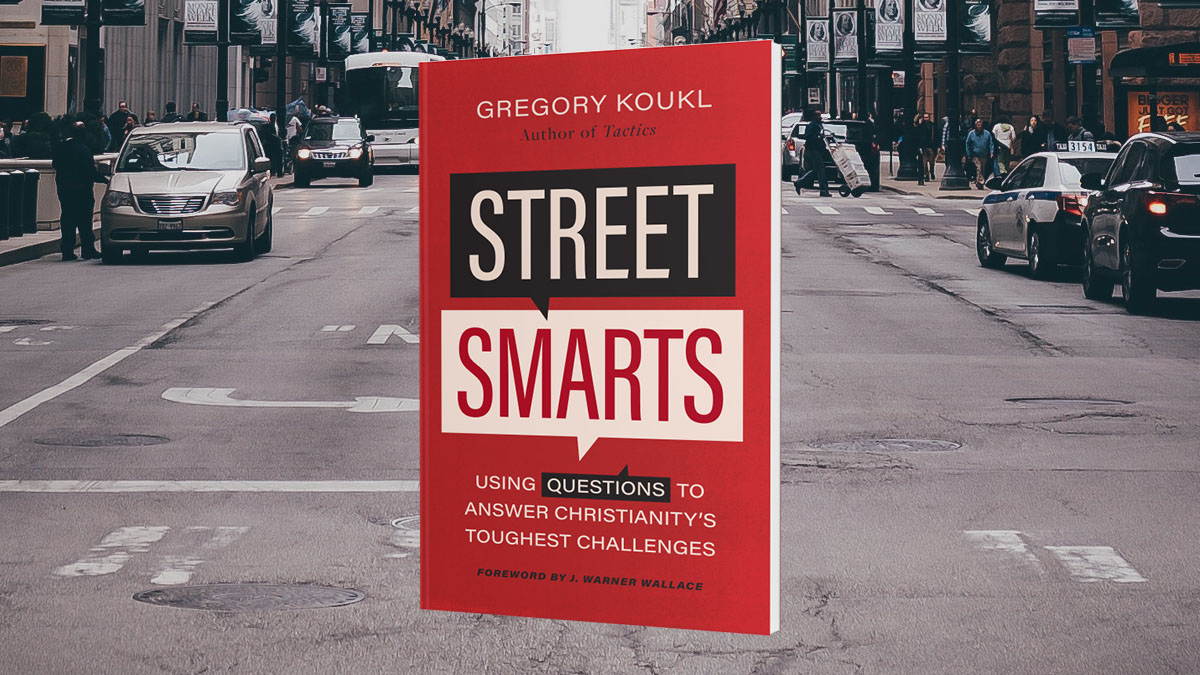

A new book by Greg Koukl was written to equip Christians to dialogue from a confident and informed faith. As a thank-you for a gift of any amount to the Colson Center this month, we’ll send you a copy of Street Smarts: Using Questions to Answer Christianity’s Toughest Challenges. The book is a guide through the hot-button issues with wise responses to arguments against Christianity. Give today at colsoncenter.org/September.

For more resources to live like a Christian in this cultural moment, go to breakpoint.org.

This Breakpoint was revised from one originally published on May 17, 2016.

Have a Follow-up Question?

Up

Next

Related Content

© Copyright 2020, All Rights Reserved.