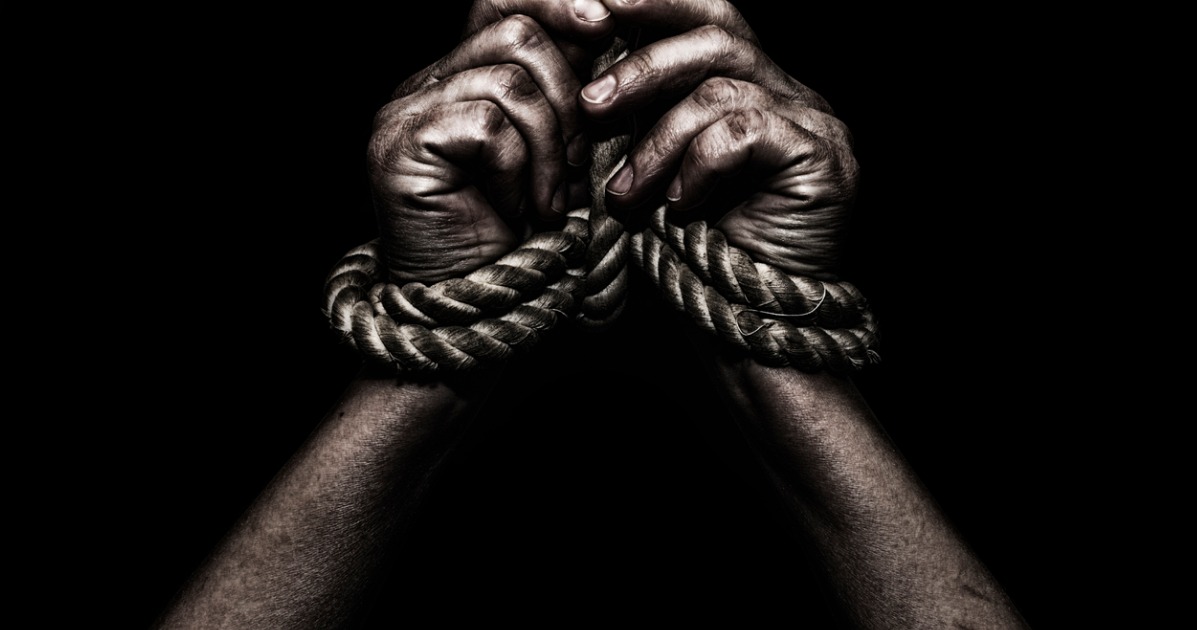

As inconceivable as it is to us today, there was a time when intelligent and moral Christians defended the heinous practices of American Slavery. It is frightening that they could be so captive to their culture that they couldn’t see the sin they supported. It is even more frightening that we are just as capable as falling prey to our own cultural whims and priorities.

Some years ago, a respected pastor addressed a crowd gathered in Charleston, South Carolina. They had come together for the dedication of a new ministry, a ministry specifically created to reach out to African Americans in the racially divided South. The preacher noted that the organizers had stood up to outside pressure by those who said that this venture was poorly thought out and could never overcome the obstacles it faced. He further thanked God that they had persisted and that now the grace of the gospel could come to this underappreciated community in their fair city.

As much as we today may wish to applaud these fine words and the sentiment behind them, there is a catch. The preacher in question was James Henley Thornwell, and, on this day in 1850, he offered a thoroughgoing defense of American Slavery and, what is more, he appealed to the Bible to do so.

To say that this is rather unnerving is to put it mildly. It would be far more comforting for us today had the advocates of slavery in our recent past been the outcasts of polite and Christian society. Instead we find that some of the keenest voices in American history defending this abhorrent practice came from highly respected theologians who had well-deserved reputations for their knowledge of Scripture, careful reasoning, and compassion for the lost, even the lost among those enslaved in their midst.

We might rest more easily if the pro-slavery sentiments came only from obscure, heterodox, and ill-informed amateurs, but the church today must face the fact that some of the strongest attempts to justify American Slavery came from prominent, orthodox, and professional theologians. Men like Thornwell, pastors like Thornton Stringfellow and theologians like Robert Lewis Dabney, all used their great minds and skill to justify an injustice. This is a problem.

Despite the fact that the biblical testimony possessed a trajectory of emancipation, demanded legal protection from abuse, unconditional sanctuary for escaped slaves, time limits on slavery’s duration, and the death penalty for manstealing, which was, after all, the basis of the entire American enterprise, theologians worked to support the “peculiar institution” from the Word of God. Where did they go wrong?

A significant portion of their contention rested on what we might call technicalities. For example, they regularly relied on arguments from silence, which, while not really fallacious, are not the strongest statements to be made. This becomes significant when we see how very often their case was, in effect, “If God had not wanted us to have chattel slaves in perpetuity, He would have said so.” This is little more than dodging the question. It’s saying we have to have a specific command NOT to treat human beings as less than animals before affording them the respect owed to the divine image they bear.

One line of argument was that they very often wrote as though legitimate practices and positive side effects enabled and endorsed all practices and uses. They often made note of times in the Bible when people the text called servants or slaves were treated well or held up as a hero. This, apparently, meant that the Bible took no issue with the abusive slavery of America. To reverse the image used by Dabney at one point, it’s as though legitimate parental rule over children legitimized child abuse.

Another problem was that they did not distinguish sufficiently between description and prescription, between what sinful humanity did in their practice and what God had in mind for His principles. No doubt, many ancient peoples practiced an overt kind of slavery, whether in the Patriarchal age or the time of the Early Church. No doubt, too, the biblical authors at times made mention of this fact without comment.

However, what these theologians did not note was how contradictory was ancient slavery to some very specific laws in the Bible about how slaves were to be treated. The laws of the Old Testament and the testimony of the New were subversive, undoing the practice of slavery as it was manifested and undermining any claim to unlimited power and rights of the supposed master over the supposed slave.

One interesting things these otherwise keen minds failed to see is how their own words undermined their assertions. One thing which is at the core of many such arguments is that slavery is for the good of the enslaved, that by bringing these pagan Africans into the thralldom of Christendom, they may be improved. By the general revelation of strict discipline their morals may come more in line with the will of God, and by the special revelation of the preaching of the Gospel, they may be saved from their sins.

However, at the same time, they used the laws governing Israelites’ treatment of non-Israelite slaves to justify their treatment of non-white, non-Christian slaves. Yet, were the African slaves to become Christians, as they all claimed was their goal, this would, by their own arguments, bring them under the law governing Hebrew slaves, making all legal constraints such as term limitations come into play as well as the blessings of the Covenant to be treated as full equals.

I would contend, however, that the fundamental obstacle between these men and the truth of the Bible was not so much a failure to understand the Word of God but an inability to accurately see their own culture. They carefully noted that a practice going by the name slavery was part of the formal system of the biblical order, and from this they derived that their own slavery was acceptable. What they did not note was just how inconsistent was the reality of their system with the statements of the Bible and even their own high-minded principles.

The only way they could justify American Slavery from the Bible was through being willfully blind to the reality of American Slavery. Creating mental Potemkin villages, they imagined a world where slaves were well-treated, instructed in the things of God, and were, if anything, grateful the opportunity to rise above their previous lives.

For all their talk about the acceptability of slavery in the Bible, these men of the Word did not talk about the manstealing which was the foundation of the entire American slave system. They did not talk about the image bearers of God stacked like cordwood and lying in their own filth for the duration of the “Middle Passage.” They did not address the rampant sexual abuse of African American women at the hands of their good Christian masters. They did not mention the beatings and lynching of African American men, all for the “crime” of desiring freedom.

They did not note that, for all their talk of the benefits towards godliness found in suffering, this was a benefit that they did not see fit to endure themselves, or any other white person, leaving it only for those of a “lesser” race.

In a great fit of irony, one of the surest predictions of the cost of this faulty thinking came in that same 1850 sermon by Thornwell. Sounding like nothing quite so much as the dire, repentant words of President Lincoln in 1865 looking back on the previous four years of slaughter, he unintentionally predicted what was to come, saying

“What disasters it be necessary to pass through before the nations can be taught the lessons of Providence, what lights shall be extinguished, and what horrors experienced, no human sagacity can foresee. . . [this] shall open their eyes to the real causes of their calamities, and learn the lessons which wisdom shall evolve from the events that have passed. Truth must triumph. God will vindicate the appointments of His Providence.”

God would indeed vindicate his providence in a short time, though it likely did not take the form this Southern Patriot would imagined or preferred as his beloved Charleston and many other Southern towns felt Lincoln’s “blood drawn with the sword” for “all the blood drawn with the lash.”

For all their careful understanding of the Bible, for all their dutiful prayers, for all their concern for the lost, they could miss something so plain. For all their desire to be led by Scripture, they let their contemporary cultural drift drive them into supporting a horror. These intelligent and careful students of God’s Word could write beautifully about things which we can applaud and endorse . . . and yet. And yet they used their God-given abilities to endorse and applaud a horrible crime against human beings and against the One whose image they bore.

They didn’t see what was right before them. What is it that we don’t see? I don’t mean the things about our culture which we reject as immoral today. I mean what are those things about our world which cut against the grain of God’s revelation which we yet defend, not because we don’t know our Bibles but because we can’t see beyond our cultural blinders.

The warning for us today is that we are not immune. We must always ask ourselves, what drives our understanding, the transitory world around us or the enduring Word of God? How much is our cultural worldview determining what we then falsely deem to be the Christian Worldview?

We’ll always fall short in some ways. We cannot be fully free of our cultural trappings, but we can work to minimize their effect. We can keep up with the issues and consider the unspoken assumptions society pushes upon us. We can consult with scholars and listen to people who disagree with us. We can read up on history to see how other cultures have been blind to their own age. By constantly reminding ourselves that we might be wrong, by going before God in prayer, and by immersing ourselves in His Word, we may acquire a sure North Star to guide us through our culture’s whims. Only by continually reorienting ourselves to Him who is above all cultural moments can we avoid becoming enmeshed in our own all-too fallible age.

[Editor’s Note: This article is a summary of a paper presented at the Evangelical Theological Society in Denver on November 13, 2018.]