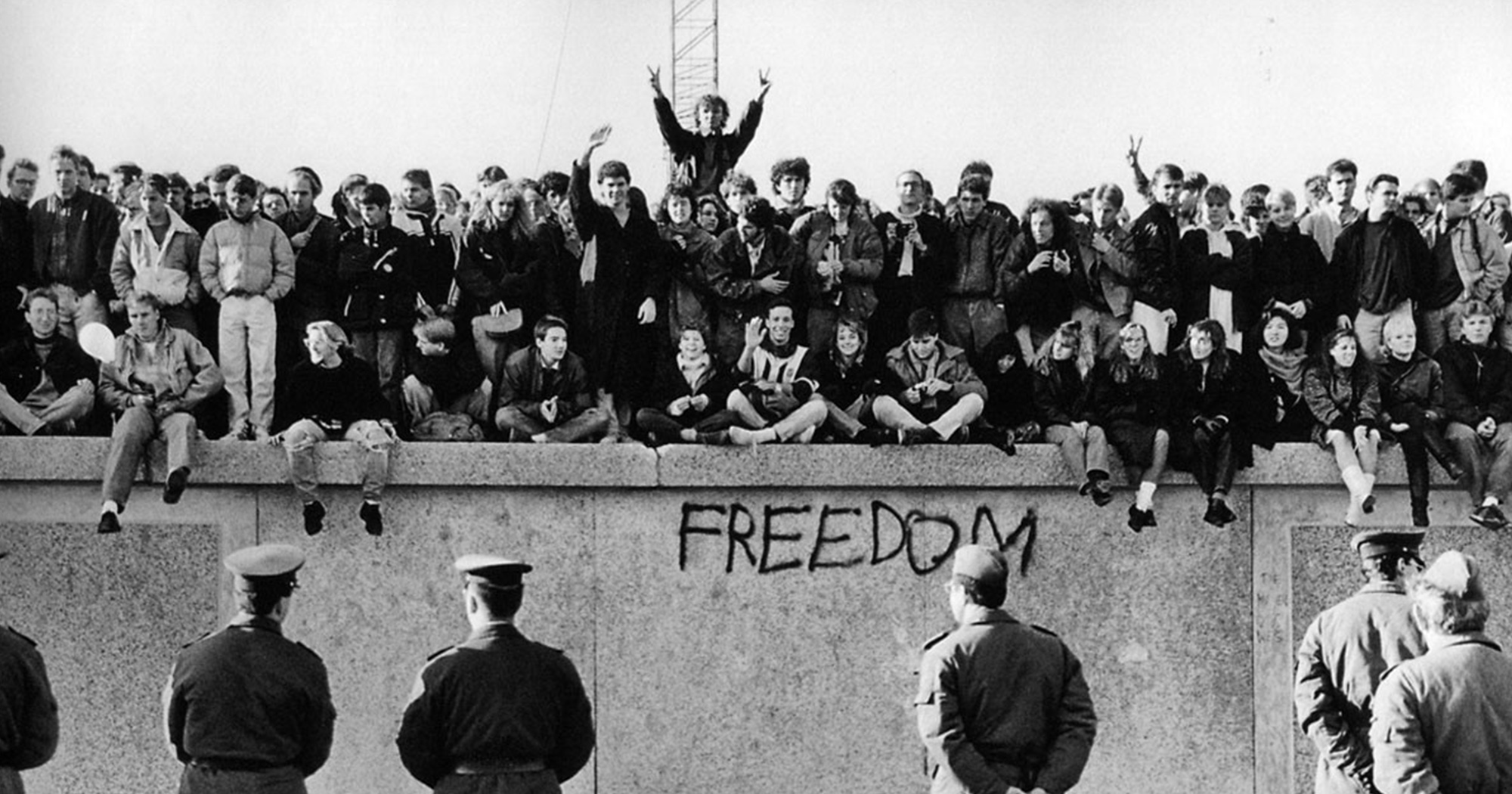

November 9, 1989 was a glorious day, a day unlike any I’d ever seen and likely won’t ever see again. It was like the old movies from the end of a war, which, in one sense, it was. People dancing in the streets, celebrating the reality that the unimaginable had happened. Peace had come at last.

I was 15 when the Berlin Wall came down. Old enough to know it was a big deal; not old enough to remember a time without it. Just the previous summer I’d visited it with my family. It was a surreal experience, well-armed troops, guns pointed toward their homeland.

It is hard for us, 30 years on, to remember what that moment was like, particularly for the Germans. For 75 years, they’d lived with a knife at their throat. It would take a very old man to remember a time when Germany was not at war, in one way or another. Since that fateful summer of 1914, the land of Bach and Luther had been an armed camp, admittedly one quite often of their own making.

It wasn’t for our Teutonic friends alone that this day was for dancing. Since 1945, when American and Russian troops went from allies to adversaries with whiplash speed, virtually the entire globe was gripped in the chilly embrace of the Cold War. While we now fear a rogue group with a single bomb, then we lived in terror of tens of thousands of nuclear warheads ending life as we knew it. On that day in 1989, the fires of the Cold War died.

The fall of the Wall symbolized the end of a totalitarian nightmare. With a death toll dwarfing Nazism’s dreadful tally, Communism turned a third of the world into a police state such as no one had ever seen.

With the death of Communism, the final obstacle to Enlightenment liberalism was cast on the ash heap of history. There was nothing left for us to do but to watch as the glories of democracy, capitalism, and liberalism seeped across the frontiers of its vanquished opponents.

Many looked at the Iron Curtain as an immutable fact, even something to be admired. Others saw it for what it was: a tottering tyranny to which the demands of human dignity required implacable opposition. The likes of Reagan, Thatcher, and Pope John Paul II saw in Marxism’s blood-red banners not liberation but oppression. They saw Communism as something not only that should be opposed, but that it could be.

And it worked! Faster than even the most optimistic opponents could have dreamed, the deadly edifice of Communism tumbled down with the fractured walls of a no-longer-divided Berlin. No more Stasi, no more secret arrests. The forces of freedom had faced down their own Black Gate, and the Men of the West had won.

The enthusiasm was infectious. It seemed that even the always-dour traffic reports stopped advising a little extra time going into work. People hoped for the ever-elusive “peace dividend,” a great release of economic treasure now that we no longer had to live on a war-footing.

Some even went so far as to declare and End of History. While this contention was not as simplistic as it may sound, there was in the air of that day an expectation that something fundamental had changed in the human condition. With the death of Communism, the final obstacle to Enlightenment liberalism was cast on the ash heap of history. There was nothing left for us to do but to watch as the glories of democracy, capitalism, and liberalism seeped across the frontiers of its vanquished opponents.

But a funny thing happened on the way to Utopia. It wasn’t but weeks later that American forces, now relieved of their fears of a Soviet reply, leapt into action in Panama. A year later, the US had assembled a new coalition, establishing a (still-ongoing) presence in the Middle East. In Europe, without the guiding darkness of Marxist beliefs, the Yugoslav federation fell into a bloody separatist war, and this is not even to mention the horrors of Somalia, Rwanda, and host of other simmering slaughters across the world.

Then, like a slasher flick where the long-dead villain rises back to life, a specter from the past came crashing into our hearts one September morning. Religion, it seemed, was not left behind in the ideological clashes of the 20th century but still a going concern for a host of those as intent on global domination as had been any Petrograd intelligentsia of a century before. We now have soldiers fighting in Afghanistan who weren’t even born when the war began.

This worked fine so long as there was an enemy to fight. But, when our foe had suddenly gone the way of Dodo, we found ourselves at a loss to explain why “my” freedom should be constrained by “yours.”

So, how are we doing today? Has the time since the “end of history” fulfilled the promise of those heady days 30 years ago? Have the virtues of liberty and the priority of human dignity captured the hearts of the nations? Hardly.

Everywhere we look we see the abdication of freedom and the embrace of history’s worst ideals. It’s not just China, Russia, and Venezuela rounding out our list of usual suspects. Filipinos, Hungarians, Poles and others have latched onto the fallen star of authoritarianism, seeing in strongmen a chance to hold their ground against the chaos unleashed in liberty’s triumph. Even in the freedom-loving Anglosphere, once the bastion of democracy against tyranny, increasing numbers of people seek hope in state power, whether warmed-over Marxist or Alt-Right.

How did it come to this? How did dancing on the ruins of the Berlin Wall mutate into an ever-expanding embrace of the very values it represented? In the 20th century, we ran on the inertia of the Christian worldview, dressing up in Enlightenment lingo principles of human dignity derived from the Bible. This worked fine so long as there was an enemy to fight. But, when our foe had suddenly gone the way of Dodo, we found ourselves at a loss to explain why “my” freedom should be constrained by “yours.”

In our fight for victory over tyranny, we forgot what made freedom possible. We forgot that without a firm foundation in a humanistic understanding of dignity, liberty inexorably turns into a squabble between various in-groups.

If we in the West wish to preserve our liberties, we must build on the Bible’s principles of human dignity. Without these things, without a basis rooted in something sterner than the will of the malleable majority, our precious democracy will collapse as surely as Communism’s concrete boundaries turned to dust.

Timothy D. Padgett, PhD, is the Managing Editor of BreakPoint and the author of Swords and Plowshares: American Evangelicals on War, 1937-1973

Image: Google Images

Topics

Berlin Wall

Christian Worldview

Cold War

Communism

Democracy

History

Liberty

Marxism

Soviet Union

Tyranny