Why is it that our political discussions have become so rife with anger and vitriol? In America, opinions have taken the place once held by religion.

In his wonderful new book, “Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times,” Rabbi Jonathan Sacks makes the point that we in the Secular West are still a moral people. We still hold ourselves to a standard. The problem is that, in an atomized age, we no longer have an agreed upon standard. Everyone is setting their sails toward their respective moral horizons, and we’re thus drifting further and further away from one another. Says Sacks:

“We give to charity. We have compassion. We have a moral sense. But our moral vocabulary switched to a host of new concepts and ideas: autonomy, authenticity, individualism, self-actualization, self-expression, self-esteem.”

The morality to which the West ascribes is ever more personalized, in other words. These various moralities aren’t connected to one another because they are not connected to anything transcendent. They are something like aesthetic judgments—matters of personal discretion and taste.

It’s hard to think of a worse cultural climate in which to discuss politics. In such an environment, opinions—particularly political opinions—take an unhealthily important place in one’s life.

You see, traditionally our faith gives us principles, those principles give us convictions, and it’s from those convictions that we derive our opinions.

The morality to which the West ascribes is ever more personalized, in other words. These various moralities aren’t connected to one another because they are not connected to anything transcendent. They are something like aesthetic judgments—matters of personal discretion and taste.

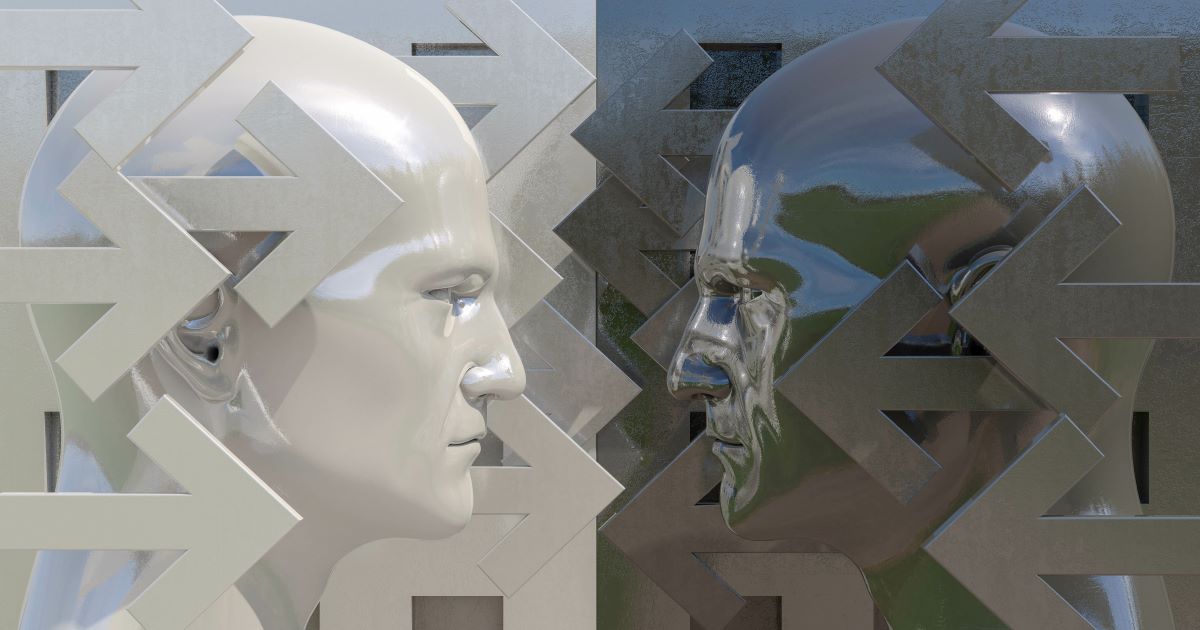

Picture a tree: our faith is the deep root structure, our principles are the tree’s trunk, our convictions are branches, and our opinions are twigs. The twigs aren’t irrelevant to the roots, to be sure, but neither is it the case that the roots are contingent upon the twigs.

If you want to understand the vitriol found on social media posts regarding politics, you have to understand that in relegating faith to the periphery, secularism has inverted the old paradigm. Our opinions now have the onerous task of serving as roots while our faith has become a mere twig.

To confront a person’s opinions in such a culture is to challenge their core identity. You aren’t plucking a leaf when you show that person that they’re wrong, you’re uprooting their whole being.

As Christians, we ought to keep all this in mind as we go about discussing politics. You see, it may seem silly that someone would become enraged about face masks, for example, but they themselves are not silly. They’re searching for meaning like everyone else and are likely feeling the unnerving sway that comes with root rot. They’re in need of help, not scorn.

To confront a person's opinions in such a culture is to challenge their core identity. You aren't plucking a leaf when you show that person that they’re wrong, you're uprooting their whole being.

Remember C.S. Lewis’ admonition that the most banal person with whom you interact will one day either become so heavenly that if you saw them today you would be tempted to worship them, or so hellish that if you saw them today you would cover your eyes in terror.

Lewis goes on to say that we’re all helping one another along, either to become more heavenly or more hellish. And that’s the real choice, isn’t it: between heaven and hell.

We all probably overestimate our ability to move our friends Right or Left and underestimate our ability to move our friends up or down, to heaven or hell. This is good news, it seems to me, because it means that we really can have a role in grounding our friends’ opinions in something transcendent. This will lead to a shared vision of morality and a healthier politics; a point Sacks makes:

“Recovering liberal democratic freedom will involve emphasizing responsibilities as well as rights; shared rules, not just individual choices; caring for others as well as for ourselves; and making space not just for self-interest but also for the common good… If we care for the future of democracy, we must recover that sense of shared morality that binds us to one another in a bond of mutual compassion and care. There is no liberty without morality, no freedom without responsibility, no viable ‘I’ without the sustaining ‘We.’”

In emphasizing evangelization, my point is not to minimize the importance of politics. No, none of this is to say that we ought not discuss politics. But it is to say that any political project unrooted from a shared vision of morality is on thin ice to begin with, so it naturally follows that we ought to prioritize the arduous task of gospel-witness and moral formation. For though we walk in the flesh, we are not waging war according to the flesh, after all.

Dustin Messer is Worldview Director at Christian Academy in Frisco, TX and Curate at All Saints Church in Downtown Dallas. You can follow him on Facebook and Twitter.